The Ringstrasse: Schorske, Olsen, and Bourgeois Self-Representation

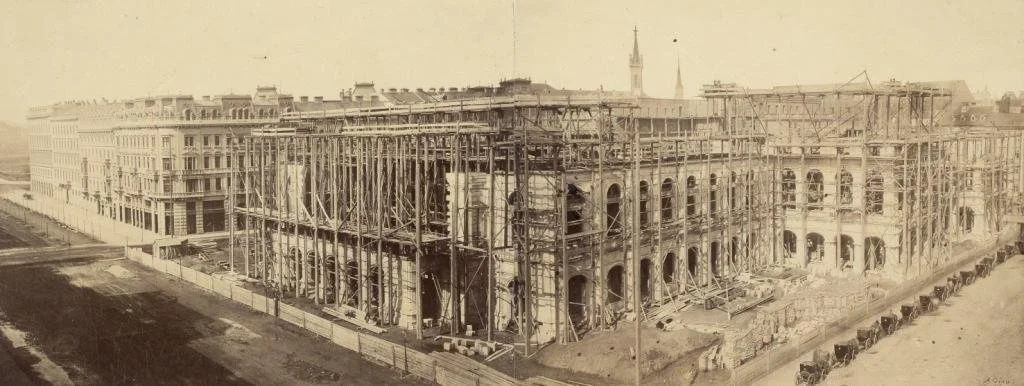

Construction of the Opera, by Andreas Groll. 1865. Photograph. (Wien Museum, Vienna). [Source]

In 1994, a volume of essays entitled, Rediscovering History: Culture, Politics, and the Psyche, edited by Michael S. Roth, was released in which several historians contributed original research and analytical reflection. [1] All of these essays relate, in some way, to the diverse methodological, conceptual, and theoretical insights articulated by intellectual historian Carl E. Schorske. Roth, in his introduction to Rediscovering History, provides a practicable avenue through which one can situate herself or himself in relation to Schorske’s own research goals as discussed in his 1980 book of essays (some of which were published earlier) entitled Fin-de-siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture. [2] Upon its publication, Fin-de-siècle Vienna became an inflection point in Schorske’s career as a historian.

Roth points out that “[Schorske]…described his project…as the product of his resolve ‘to explore the historical genesis of modern cultural consciousness, with its deliberate rejection of history.’” [3] In Schorske’s words, “The modern mind has been growing indifferent to history because history, conceived as a continuous nourishing tradition, has become useless to it.” [4] Roth extends Schorske’s above-mentioned resolve and thereby claims that he is “the historian of de-historicization.” [5] Indeed, Schorske “describes how the moderns in Vienna cut themselves free from history,” yet at the same time, Schorske “describes this [process] historically.” [6] Schorske’s objects of historical analysis do so through their embodiment and embrace of the liberal bourgeois historicist eclecticism that was so popular in the nineteenth century.

While there is much to be gained by a thorough, analytical review of each of the essays in Fin-de-siècle Vienna, the text’s second chapter, “The Ringstrasse, Its Critics, and the Birth of Urban Modernism,” merits particular attention inasmuch as it is both 1) a unique realization of the research goals explicated earlier in the book’s introduction, and echoed by Roth et al., and 2) a source of a concrete historical site of negotiation and confrontation that is interpretively ‘productive’, as far as the praxis of intellectual history is concerned. [7] Furthermore, and only in so far as it serves to concretize these research goals, a contrastive analysis placing Fin-de-siècle Vienna in conversation with relevant sections of art historian Donald J. Olsen’s later (1986) tome, The City as a Work of Art: London, Paris, Vienna, will flesh out pressing questions of moment, meaning, and motive through a more or less well-defined object of historical analysis. This object is the Viennese Ringstrasse and its implications for a historicized comprehension of the linkage between politics and culture inasmuch as they are reflected in the narratives of conflict and/or assimilation between an ascendant liberal bourgeoisie and an encrusted neo-absolutist aristocracy. [8] More specifically, this investigation will consider how Schorske and Olsen theorize bourgeois self-representation as far as this is embodied or related to the construction and debates over the Ringstrasse.

One of the sites of very important work on social and political and cultural history in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries is that of the urban metropolis; in particular, the emergence of European cities. Works such as those by Schorske and Olsen allow one to see very clearly imperial politics at work, i.e., the domestic politics of an imperial government. In both works, one sees how the imperial structure of a nation state directing social policy, health regulations, and urban life were stimulated by the very intense needs of overcrowding, sanitation, and problems of social control. As far as the experience of the urban metropolis goes, cities were sites related to self-conscious representation, both to the world and to the nation. Schorske’s text excels in carefully drawing out how the self-expression of the city related to the sudden victory of Viennese bourgeois liberals. The ascendency of the liberal bourgeoisie as a social class was accompanied by their concerted effort to construct a representational system unique to them in the monumental construction projects on the Ringstrasse. In the Viennese case (1870-88), it is crucial to highlight the fact that, similar to Paris (1853-69), one generation witnessed the large-scale demolition and reconstruction of its urban centers. Throughout Fin-de-siècle Vienna, Schorske emphasizes the very sudden victory of a weak Bourgeoisie in the Austro-Hungarian empire in which liberal visionaries are suddenly given power in the midst of an encrusted and creaky, multi-national empire that was endowed with centuries of ossification and a rather complex cast system. Following this period of political success, the ascendant liberal class was defeated just as quickly as they rose to power.

While a survey knowledge of the Austrian Empire (i.e., das Kaisertum Österreich, 1804-1867) is not a prerequisite for tracking with Schorske’s argument, it is very helpful, especially as he begins it in the trenches of the Austrian constitutional reforms of the 1860s. Survey knowledge of the October Diploma of 20 October 1860 will also prove helpful before embarking on Schorske’s analysis of urban modernism and its role in the Austrian bourgeoisie’s interaction with the entrenched aristocracy in Vienna. We learn at the outset that “the liberals of Austria took their first great stride toward political power in the western portion of the Habsburg Empire and transformed the institutions of the state in accordance with the principles of constitutionalism and the cultural values of the middle class.” [9] In light of this liberal ascendancy (which would be lost by century’s end), Vienna was transformed into a “political bastion,” an “economic capital,” and the “radiating center of [liberal] intellectual life.” [10]

Roth argued that “Schorske [has shown how] history thrives on making connections, on relativizing claims for autonomy made by various intellectual and cultural movements.” [11] “History,” Roth continues, “is an essentially combinatory activity; and intellectual history can only exist by bringing together cultural productions within a perspective which privileges temporal connectedness.” [12] Schorske’s chapter on the Ringstrasse is an enterprise of combinatory activity vis-à-vis its narration of crisis and rupture with synchronic and diachronic threads. This combinatory work is most evident in Schorske’s treatment of social class and the life of art and architecture beginning in the 1860s. Schorske notes, “The liberal rulers, in an urban reconstruction which dwarfed that of Napoleon III’s Paris, tried to design their way into a history, a pedigree, with grandiose buildings inspired by a Gothic, Renaissance, or Baroque past that was not their own.” [13] More explicitly, the language of Fin-de-siècle Vienna is that of a small, condensed elite moving across space and time in an accelerated framework in which major changes happen, unleashing a crisis of class-based self-representation, among other things. More than does Olsen, Schorske goes through forms of Ringstrasse architecture as a totality of eclectic aspiration and understands the Ringstrasse as “embodied in stone and space a cluster of social values.” [14] We learn that “the planning of the Ringstrasse was controlled by the professional and the well-to-do for whose accommodation and glorification it was essentially designed.” [15]

His chapter on the Ringstrasse comprises an introduction and five subsequent parts. In part I, Schorske uses art-historical and technical vocabulary to discuss the significance of the ascendant liberal building projects on the Ringstrasse. He discusses its transformation from an undeveloped military glacis to something quite different: “What had been a military insulation belt became a sociological isolation belt.” [16] In fact, “the public buildings [on the Ring] float unorganized in a spatial medium whose only stabilizing element is an artery of men in motion.” [17] Already in part I, Schorske begins planting the seeds for what could be understood as the attempt at bourgeois-aristocratic rapprochement which is substantially deconstructed in part V. Schorske argues here, “Like the Opera and the Museum of Art History, the Burgtheater provided a meeting ground for the old aristocratic and new bourgeois élites, where differences of caste and politics could be, if not expunged, at least attenuated by a shared aesthetic culture.” [18] In his discussion of the utilitarian, transportation-focused urban modernist architect, Otto Wagner, Schorkse details the decline of ascendant liberalism with the Postal Savings Bank office, “whose headquarters Wagner built, [which] bore witness to the parallel revitalization of the old religious forces in new social guises.” [19] In fact, “the institution was created for the ‘little man’ as a state-supported effort to offset the power of the big banking houses—the ‘Rothschild party.’” [20]

For Schorske, the Ringstrasse is a site of confrontation, highlighting the multipolar and differentiated self-understandings of social class. In the first sense, the contrastive elements between the neo-absolutist aristocracy and the ascendant liberal bourgeoisie, and in the second sense, an internecine war of self-understandings with the various inflections of bourgeois identity as exemplified in Sitte and his artisanal context on the one hand, and Otto Wagner and his “second level” ascendant liberal context on the other. Perhaps the central question of Schorske’s chapter – albeit one that is more systemic and muted – is how does one define bourgeois?

Schorske and Olsen both write of an era in which progress is a teleological conception structured by a linear movement toward the Enlightenment vision of perpetual forward movement. Nineteenth-century culture makers are at their highest point, and they proceed to look back to the past and pick and choose the styles that appeal to them, usually aristocratic styles. The badge of one’s cultural status related to how one discriminated between royal and aristocratic styles of the past. Olsen’s text was an interdisciplinary intervention in traditional urban historical analysis published in the 1980s. Indeed, Olsen writes,

“The stress on the superficial and the luxurious does not arise from a spirit of frivolity, but from the conviction that societies better reveal themselves at play than at work. It is when art takes over from utility that the outward forms of cities become significant. A pure and abundant supply of water, street networks adequate to the traffic, housing that provided the minimum of shelter, public transport that met the needs of the local economy: all cities had to provide these. Industrial cities, strictly speaking, provided little more.” [21]

There are five sections in the text: the city as luxury, the city as monument, the city as home, the city as playground, and the city as document. Generally speaking, Olsen sets out to “examine…London, Paris, and Vienna…during their period of most significant growth, the century preceding 1914.” [22] “It was then,” he argues, “that each of them acquired its present shape and aspect. Each underwent a crucial upheaval that both irrevocably altered its physical structure and established a pattern for future change: in London, the cutting through of Regent Street by George IV; in Paris, the radical surgery performed by Louis napoleon; in Vienna, the laying out of the Ringstrasse” (ix). Olsen seeks to demonstrate how each city, rather than a haphazard agglomeration of chaotic interaction, was in fact deliberately conceived as a holistic picture-narrative, a chef-d’œuvre aimed at institutionally and architecturally echoing the values of the wealthy and to serve as a spatial nexus for elites. At the same time, he clarifies at the outset of his project that “[he has] approached [his] three cities as objects to be cherished and understood rather than as evils to be exposed, as works of art rather than as instances of social pathology.” [23]

At the outset, Olsen presents a somewhat political stance regarding his historical analysis of cities in general. For him, the city is a spectacle, it is constitutive of a certain kind of a way of living that is inherently linked to pleasure and leisure, rather than to things one normally associates with urban life: crime, disease, class strife, etc. Olsen’s scope is considerable, taking into account varieties of modernity, architecture, and symbolic systems; this is also true chronologically. [24] Olsen’s book stands out in its intensely comparative structure; he concentrates on the nineteenth century broadly conceived, beginning with the post-Napoleonic era to monumentalization of late century and early twentieth century. Its broad scope is an unusual pairing with its sharp analytic and interpretive comportment as an example of an intervention in urban history.

In his chapter, “The City as Monument: The Vienna of Franz Jospeh,” Olsen’s analysis of the creation of the Ringstrasse is all encompassing (cf. fn. 18). At points in his analysis, he gives highly detailed and at times, ground breaking, analytical deconstruction of primary sources, always sustaining a powerful descriptive force. [25] Olsen discusses the wealthy and middling classes of Vienna and how they percolated in the heart of the city in spite of tightness, discomfort, and lack of privacy. For Olsen, Viennese social life wasn’t nearly as diffused as it was in London, rather the public life along the border of the Ringstrasse was the place to be, showing how crucial monumentalizing and public spectacle were to its formation. And yet, when it comes to addressing the social significance of the Ringstrasse, or perhaps even its social composition, Olsen resorts to social categories of differentiation so wide that they almost lose historical efficacy for identifying sociocultural and sociopolitical groupings or collectivities. For example, in his chapter, “The City as Home: Social Geography,” Olsen provides this interpretation of the socio-economic composition of the Ring.

It would be wrong to exaggerate the social inferiority of the Ringstrasse. It served rather as the concrete expression of the admission to the ruling classes of both individuals and broader social groupings, who expanded and enriched the older governing class just as the Ringstrasse zone expanded and enriched the older City. […] But these were not distinct compartments, with nothing but old aristocracy in one quarter, nothing but bankers and industrialists in the other; rather, a larger than average proportion of certain groups lived in certain districts. And all groups met and mingled in the many cultural and political institutions of the great boulevard. […] The Ringstrasse can better be understood as a meeting ground than as a device for sterile social segregation. [26]

It appears that Olsen’s “ruling classes” and “older governing classes,” while still helpful distinctions, do not go far enough in conceptualizing the extent to which ascendant liberal bourgeois self-understanding—according to their own accounts—sought to construct the Ringstrasse as a stratified space that represented their newly attained power as a distinct social grouping through the use of eclectic historicism. Housing crises, an encrusted caste system, and a panoply of socio-economic factors overlooked by Olsen factor into a strong refutation of his claim of broad class mingling and his understanding that, “The Ringstrasse can better be understood as a meeting ground than as a device for sterile social segregation.”

And yet, perhaps the broadest thematic unifier across Olsen’s three cities is the theme of nineteenth century historicist eclecticism, something only true for some buildings in Vienna as a whole. Olsen’s nineteenth century pan-European world is marked by eclecticism and historicism. In other words, architects and artists harkened back to styles of the past to create the models for the urban present. Certain styles of the past evoke and symbolize certain functions, a point that is more evident in Schorske’s chapter on the Ringstrasse in Fin-de-siècle.

Olsen, furthermore, does not give as much weight to Schorske’s rupture hypothesis. As far as the question of the “meaning” of the Ringstrasse is concerned, Olsen is content with a panoply of explanations to account for conflict and differentiation in urban modernity. Speaking of the relationship between the bourgeoisie and the aristocracy, Olsen cites historian Arno Mayer, who argued that “the economically radical bourgeoisie was as obsequious [to the old aristocracy] in cultural life as it was in social relations and political behavior.” [27] While Schorske would certainly agree with Mayer’s analysis to a certain extent, it is likely that he would also point to the paradoxes, contradictions, and psychic turbulences in the careers of individuals such as Sitte and Otto Wagner to argue against such a sweeping generalization.

A particularly concerning interpretive difference between Schroske and Olsen concerns the Postal Savings Bank office mentioned above. Olsen argues the following:

The demolition of the Franz Josephs-Kaserne left space to be filled, notably by Otto Wagner’s headquarters building for the Postal Savings Bank and the new War Ministry. Visually the two buildings represented the two dominant trends of the prewar years: the one Sezessionism and the other “stripped-down classicism.” Yet both, as they face each other on opposite sides of the Ring, maintain the conspicuous monumentality inherent in the Ringstrasse tradition. Attempts to assimilate Otto Wagner into the subsequent so-called modern movement require ignoring or playing down the aspects of his genius that belong to an earlier, less restricted view of the representative function of civic architecture. Just as his Stadtbahn stations raised the daily journey from home to work to the level of heroic art, so the Postsparkasse gave to the saving efforts of the ordinary man or woman a fittingly dignified setting. [28]

Granted, Schorske’s goal was never to “assimilate…Wagner into the…modern movement.” Indeed, his work precisely highlights “[Wagner’s genius, which belonged] to an earlier, less restricted view of the representative function of civic architecture,” throughout his Ringstrasse chapter. However, what cannot be overlooked is Olsen’s shocking claim that “the Postsparkasse gave to the saving efforts of the ordinary man or woman a fittingly dignified setting.” One would have foreseen perhaps a tempering of Schorske’s allusions to anti-Semitism in the Viennese Christian socialist party; but an outright flattening of the historical linkage is a concerning oversight, and indeed laughable in light of the evidence displayed in the final pages of Schorske’s Ringstrasse chapter.

This investigation has sought to juxtapose Schorske and Olsen’s broad methodological approaches to Ringstrasse and to problematize some of Olsen’s conclusions in light of the particularistic approach of Schorske’s class-specific emphasis. It is important to read Olsen’s text in light of its large scope and vast chronology, however there are episodes where Olsen’s flattening of class differences evinces a concerning lack of attention to class matters which played such a powerful role in Schorske’s analysis, with which Olsen was certainly familiar and most likely read carefully based on the extent of textual citations attributed to Schorske in Olsen’s text. Olsen throughout evades the question of bourgeois self-representation vis-à-vis the Ringstrasse and instead fails to consider how an ascendant liberal elite made its mark on monumental architecture as a function of urban modernism and innovations in the conceptualization of art history and architecture in the late nineteenth century. While Olsen and Schorske both share general thematic conclusions: eclecticism and historicism as nineteenth century topoi and a general understanding of class difference, perhaps Schorske’s work is a testament to the utility of particularistic, case-based analysis with heavily research, image-based analysis. It should be noted, however, that Olsen’s work excels and even exceeds Schorske’s in its analysis of interior design and the interpretation of the interiority of space as a function of public and private lives in various city-contexts.

Works Cited

Chartier, Roger. "Intellectual History or Sociocultural History? The French Trajectories." Translated by Jane P. Kaplan. Chap. One In Modern European Intellectual History: Reappraisals and New Perspectives, edited by Dominick LaCapra and Steven L. Kaplan, 13-46. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1982.

Olsen, Donald J. The City as a Work of Art: London, Paris, Vienna. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986.

Roth, Michael S. "Introduction." In Rediscovering History: Culture, Politics, and the Psyche. Cultural Sitings, 1-7. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1994.

Schorske, Carl E. Fin-De-Siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture. Vintage Books ed. New York: Vintage Books, 1981.

Notes

[1] Michael S. Roth, "Introduction," in Rediscovering History: Culture, Politics, and the Psyche, Cultural Sitings (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1994).

[2] Carl E. Schorske, Fin-De-Siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture, Vintage Books ed. (New York: Vintage Books, 1981).

[3] Roth, "Introduction," 3.

[4] Schorske, Fin-De-Siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture, xvii.

[5] Roth, "Introduction," 3.

[6] Ibid.

[7] In the conclusion of Roger Chartier’s article in "Intellectual History or Sociocultural History? The French Trajectories," in Modern European Intellectual History: Reappraisals and New Perspectives, ed. Dominick LaCapra and Steven L. Kaplan (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1982), 42-46., Chartier notes the following: “The only definition of intellectual history presently admissible is probably that given by Carl Schorske, to the extent that he assigns it neither particular methodology nor obligatory concepts but only indicates the double dimension of a task…” Chartier then goes on to reproduce a crucial excerpt from Schorske’s Fin-De-Siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture, xxi-xxii. The edition of the text from which Chartier cites is slightly different from today’s most accessible edition (the Vintage paperback), therefore I reproduce the citation from the newer edition below: “The historian seeks rather to locate and interpret the artifact temporally in a field where two lines intersect. One line is vertical, or diachronic, by which he establishes the relation of a text of a system of thought to previous expressions in the same branch of cultural activity (painting, politics, etc.). The other is horizontal, or synchronic; by it he assesses the relation of the content of the intellectual object to what is appearing in other branches or aspects of a culture at the same time.”

Chartier summarizes, after considering the similarity between historian of nineteenth-century historiography, Hayden White, in light of the article’s engagement with French historians who have resisted engagement with developments in intellectual history, “Without necessarily saying so, those in France who attempt to understand ‘intellectual objects’ (to use Schorske’s term) concur in this definition of cultural space (and therefore of the very terrain of their study) as two-dimensional, which permits us to conceptualize an intellectual or artistic production at once in the specificity of the history of its genre or discipline, in tis relation to other contemporaneous cultural productions, and in its relations with different referents situated in other fields of the social totality (socioeconomic or political). To read a text or decode a system of thought means, then, to embrace together these different questions that constitute, in their articulation, what we can consider to be the very object of objective of intellectual history.” In the pages that follow, more critically, Chartier delimits what Schorske’s provisional definition of intellectual history can mean in a post-Foucault, and more interestingly, a post Paul Veyne world, in which, as Chartier cites from his essay, “Foucault révolutionne l’histoire,” (cf. fn. 58, p. 43), “In this world, we do not play chess with eternal figures like the king and the fool: the figures are what the successive configurations on the playing board make of them.” Towards the end of the conclusion of the essay, Chartier cites cultural anthropologist Clifford Geertz as a potential way forward for intellectual history, being sure to highlight the fact that his is not a moralizing task, but one of problematizing the internal contradictions and insufficiencies of existing historical analysis.

As far as, on p. 45, Chartier calls to mind the need for a new articulation between cultural structure and social structure that is created without falling prey to the mirror image projection or the gearbox projection (which is the fruit of the all-encompassing desire for comprehensively or totalizing history), it would be an interesting historiographical and analytic exercise to examine the ways in which Schorske’s oeuvre, especially the one under consideration in this essay, Fin-de-siècle, align with or depart from Chartier’s nuanced explication of the evolution of the French historiographical legacy.

[8] Donald J. Olsen, The City as a Work of Art: London, Paris, Vienna (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986).

[9] Schorske, Fin-De-Siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture, 24.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Roth, "Introduction," 4.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Schorske, Fin-De-Siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture, 8.

[14] Ibid., 62.

[15] Ibid., 26.

[16] Ibid., 33.

[17] Ibid., 36.

[18] Ibid., 37-38.

[19] Ibid., 90.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Olsen, The City as a Work of Art: London, Paris, Vienna, 5-6.

[22] Ibid., ix.

[23] Ibid., x.

[24] Take, for example, ibid., 64.

“For Vienna, the ‘rise of the middle classes’ had been a medieval phenomenon, with the modern age characterized by the triumph of crown, church, and aristocracy. The Counter-Reformation succeeded ultimately in turning what had in the sixteenth century been a mostly Protestant city into a wholly Catholic one, the baroque splendors of whose churches and monastic foundations gave physical expression to that triumph.”

[25] Some example of a precise analysis provided by Olsen

[26] Olsen, The City as a Work of Art: London, Paris, Vienna, 154-55.

[27] Ibid., 99.

[28] Ibid., 81.