Pointing to Christ: John Calvin on Faith, Ministry, and the Offense of the Gospel

In his commentary on Matthew 11:1–6 and Luke 7:18–23, John Calvin offers a profound theological meditation on John the Baptist’s inquiry into Jesus’ identity. Calvin begins by highlighting Jesus’ steadfast dedication to his ministry. Even as the Apostles embarked on their missions, Christ continued teaching and preaching in Galilee. Calvin underscores the significance of the term “commanding,” noting that it reveals the Apostles’ role as emissaries bound by Christ’s explicit instructions. They were not free to act according to their own judgment but were entrusted with a clear mandate to guide their message and conduct.

The Appearing Grace: Living and Waiting in Christ

The grace of God has appeared, Barth tells us, and it is no abstract concept or fleeting feeling. It is found in a person, Jesus Christ, in whom God has concluded His eternal covenant with humanity. This is why, in the Early Church, this passage was read on Christmas Day, for in the coming of Christ, “the grace of God hath appeared.” This grace, Barth emphasizes, is universal: it brings “salvation to all men.” In Christ, salvation is not reserved for a select few but extends to every person, breaking down barriers and reaching across the world. Yet grace does more than save—it also teaches. Barth reminds us that it is “grace itself and as such (incorporated in this person),” not something that precedes or follows grace, that instructs us. Grace is both the principle and the command, shaping us ethically and sanctifying us through its own power.

Angels in the Field: A Reflection on Witness and Glory Based on Barth’s CD III.3, 505

The night was ordinary, or so it seemed. Shepherds watched over their flocks in the stillness of the fields, their lives shaped by routine and the simple rhythms of the earth. But on this night, heaven broke into the mundane. An angel of the Lord appeared to them, and the glory of God—brilliant, otherworldly, and unmistakable—shone around them. It was not the kind of glory that blinds or terrifies, but the kind that enlightens, liberates, and calls. The shepherds, startled yet captivated, would soon embark on a journey that would change them forever.

Reading the Bible in 2025

Presbyterians interpret the Bible through a Reformed lens, balancing Scripture with reason, tradition, and experience. This approach allows for a critical and thoughtful engagement with the text, appreciating its complexity while remaining open to its transformative power. To read the Bible, then, is not merely to read a book. It is to open oneself to God’s grace, to the wisdom of the Christian tradition, and to the ongoing work of the Spirit in shaping lives and communities. It is to participate in a story that continues to inspire, challenge, and call us to something greater.

An Advent Devotional: Psalm 18:28

The Hebrew word for “light” in the first clause, tā-ʾîr, comes from the root ʾwr, meaning to dawn, shine, or ignite. This imagery is rich and transformative, evoking the power of God’s light to pierce the deepest darkness. The psalmist’s words reflect a profound truth: God’s presence brings not only clarity and direction but also the strength to endure and overcome life’s challenges. The theologian Karl Barth describes Psalm 18:28 as a vivid expression of God’s empowering work in the life of the believer (see Barth, CD IV.1, pp. 605–608). For Barth, the image of God lighting the psalmist’s lamp is not merely poetic—it’s a declaration of divine grace breaking into human frailty. The “lamp” represents hope, vitality, and renewal, illuminated by God’s redemptive and restorative presence. The darkness that the psalmist describes encompasses the weight of Sin, despair, and external threats, but God’s light transforms this reality, offering new strength and a future filled with promise.

A Lenten Devotional: Hebrews 1:8-12

In these passages (quoting from the psalter and Isaiah), the author of the Epistle wants to show us that Jesus Christ is superior to the angels—that he is the Lord. We labor under a misapprehension if we understand the lordship of Jesus Christ as just one among so many doctrinal points to be believed. These verses elaborate on God’s temporality (that is, his time) in Jesus Christ. The eternity of God’s throne is closely tied together with God’s endless righteousness. The righteousness of God is coextensive with the terrain of God’s kingdom, which encompasses and transcends the cosmos. Only Nothingness exists outside of God’s kingdom; Nothingness will not, however, have the last word.

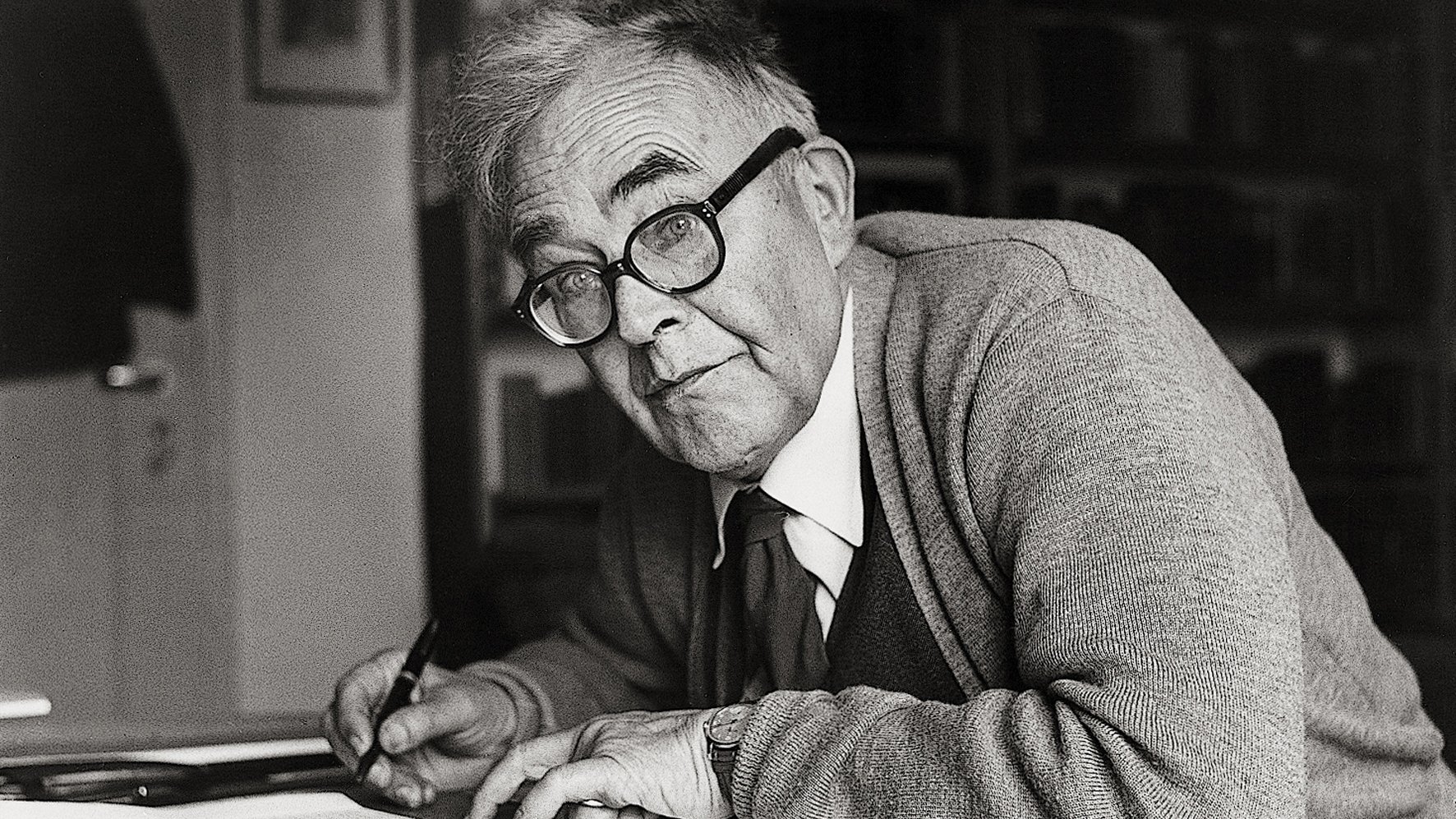

An Early Karl Barth Sermon: The Discipleship of Jesus (1907)

The following is my unauthorized translation into English of one of Karl Barth's earliest sermons: Homiletic Seminar in Bern, Summer Semester 1907: In the summer semester of 1907, his last semester in Bern before he moved to Tübingen, Barth had taken "Homiletic and Catechetical Exercises" with Moritz Lauterburg (1862-1927; since 1905 Professor of Practical Theology in Bern), according to his "Zeugnisheft" from the Bern University of Applied Sciences.

A Lenten Devotional: John 7:14–31, 37–39

At the Festival of Booths, Jesus told the crowd, “Those who speak on their own seek their own glory; but the one who seeks the glory of him who sent him is true, and there is nothing false in him.” There is a symmetry between Jesus’s activity in the world and the divine activity of the Creator God. The Father “has given [Christ] these works to accomplish in the Father’s name and for the manifestation of this name.” We also see the corollary. “Because the Father dwells in Him, the Son, it is the Father who performs the works through Him. Thus the Son is not really alone in His action, but He who sent Him is with Him” (Barth, CD III.2, p. 63). The Triune God is at work in the Christ-event, for us and for the life of the world, in the power of the Holy Spirit. Jesus’s call, “Let anyone who is thirsty come to me, and let the one who believes in me drink,” is precisely an invitation to reimagine what Lent means for us today.

Victor Turner, Christian Women, & Emancipation in Ritual

Rituals are a common thread across culture, time, and space. Examples of rituals studied by ethnographers include everything from circumcision ceremonies in central Africa to Christmas holiday shopping in megamalls across the United States. There exists a rich trove of theoretical apparatuses from which we can mine to better understand the seemingly impenetrable worlds of other religious procedures that defy Euro-American norms of liberated femininity and female emancipation. This is never more true than it is in the realm of the anthropology of theology, religion, and religious ritual.

An Advent Devotional: Phil. 1:3-11

Paul’s peace (eiréné) is literally a tying together—in Greek, the word derives from eirō (to tie together). Joined together in life’s creative wholeness, the united community of God, which “[shares] in the gospel” (koinōnia), joyfully perseveres through all hardships in thanksgiving and gratitude.

Towards an Apocalyptic Catechism

What would an ecumenical, Reformed, and apocalyptic exposition of the Christian faith look like?

On Temptation (Versuchung) in Bonhoeffer (I & II)

The reading from the New Testament on Sunday, the first Sunday in Lent, comes from Luke 4:1-13. This pericope concerns the temptation of Christ by the devil while he was in the wilderness. On reading commentaries about this passage, I came across multiple references to Bonhoeffer's essay, “Temptation,” found in various places and translated in at least two editions. I myself used the translation offered in the English edition of Bonhoeffer's Works (vol. 15, pp. 386-415). Reading the text for the first time, I was surprised by the controversial claims Bonhoeffer makes. His essay is in many respects an extension of a radical Lutheran epistemology. The very word temptation receives a thoroughgoing redefinition.

Jesus as Victim of Sexual Humiliation & Assault: Preliminary Thoughts with Tombs and Bonhoeffer

Victims of sexual humiliation and abuse likewise receive the exhaustion of the rage of the world in their bodies. Living day by day with the stigma and scars of their crisis, they suffer with the crucified one who truly knows their pain in a direct, visceral, and experiential way.

Towards a Socialistic Theology (I & II)

This distinction is perhaps one jumping off point, a conceptual springboard, from which we can begin to expand on pressing ideas in the air among left-wing Christians today. Christians together “constitute the covenant people of God” (135). What this means is that the texture of reconciliation with God must not, cannot, and will not begin with individual people reconciled to an individual God; it begins, much to the contrary, with a storied God redeeming his beloved people in space and time as the fulfillment of his freely willed determination to be the God of love in freedom, the God who wills to be with human beings for all eternity. Gorman terms the individual components of the Gospel as its “benefits.”